When goods begin their journey across oceans, they do so wrapped in layers of documentation. Chief among these is the Bill of Lading (B/L) — a document that plays multiple roles: it’s a receipt, a contract, and a title of ownership. But here’s where things get a little tricky. Did you know that there are different types of Bills of Lading, and they don’t all serve the same purpose? In the world of sea freight forwarding, two terms often crop up and confuse even experienced shippers: House Bill of Lading (HBL) and Master Bill of Lading (MBL). What do they mean? How are they different? And more importantly, why should you care?

Understanding these terms isn’t just a matter of logistics trivia — it can determine how smoothly your shipment gets delivered, how much liability you hold, and whether your cargo arrives without delays. If you’re a freight forwarder, shipper, or importer navigating international waters, getting a solid grip on these documents can help you avoid unnecessary complications. So let’s dive into the depths of House and Master Bills of Lading, unravel their differences, and understand why these differences matter in sea freight forwarding operations.

Defining the basics: What is a Master Bill of Lading?

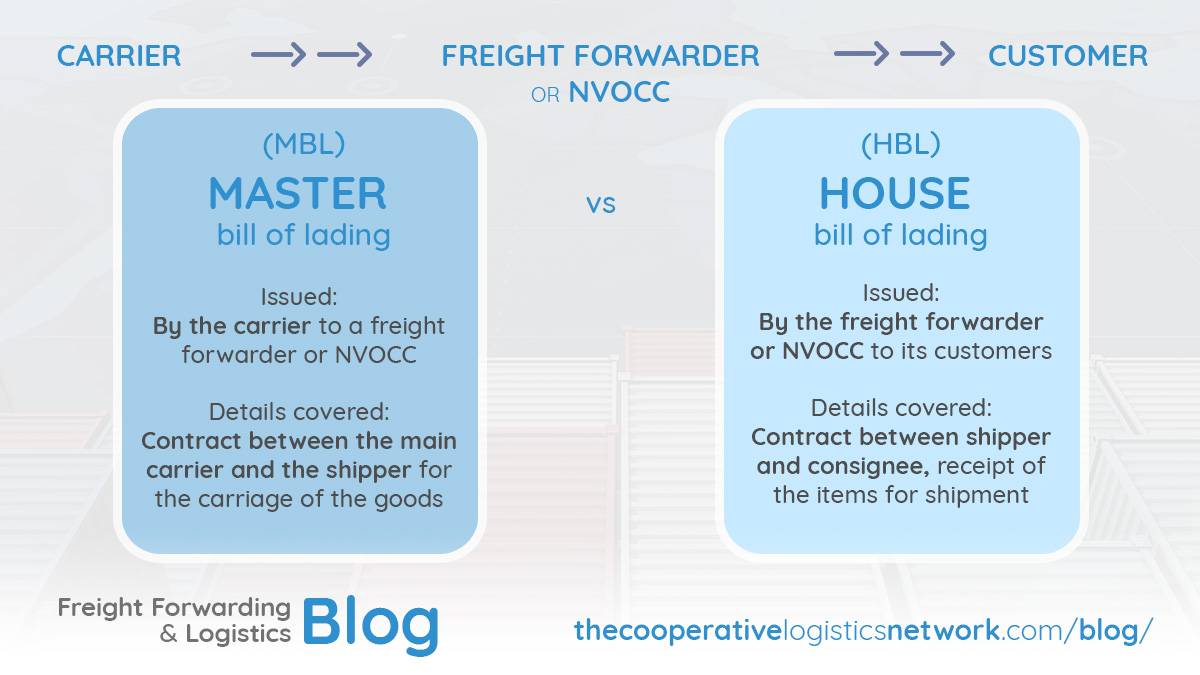

The Master Bill of Lading (MBL) is issued by the shipping line or carrier to the Non-Vessel Operating Common Carrier (NVOCC) or freight forwarder. It represents the actual contract between the carrier and the entity booking space on the vessel. This document contains details such as the origin and destination ports, the vessel name, the cargo description, the container numbers, and the consignee and shipper — typically, these will be the names of the freight forwarder or NVOCCs rather than the final customer.

Why is the MBL important? Because it’s the legal document that binds the shipping line and the freight forwarder. The ocean carrier uses it to acknowledge receipt of the cargo and to specify the terms and conditions under which the goods are being transported.

For instance, if a logistics provider in Hamburg is booking space on behalf of multiple customers, they’ll receive one Master Bill of Lading from Maersk or Hapag-Lloyd that reflects the overall booking — not the individual customers’ information. This overarching document is essential for the shipping line’s operations and customs processes.

The House Bill of Lading: A freight forwarder’s responsibility

On the other hand, the House Bill of Lading (HBL) is issued by the freight forwarder or NVOCC to their individual customers — the shippers or consignees. This document mirrors much of the information found in the MBL but is directed toward the actual importer or exporter. It is the contract between the shipper and the forwarder, rather than the carrier.

The House Bill of Lading helps in consolidating shipments. For example, if an NVOCC is moving goods from multiple small exporters in Shanghai to buyers in Rotterdam, it might book a container with an ocean carrier and get an MBL in their name. Then, it issues separate HBLs to each of its customers, detailing the specific cargo and consignee for each portion of the shipment.

This layered documentation ensures that the end-users (the importer or exporter) deal directly with their freight forwarder rather than with the ocean carrier. It also gives forwarders more control over the shipment, including flexibility in handling delays, rerouting, or even arranging customs clearance on behalf of the client.

Sea freight forwarding and the interplay of HBL and MBL

In sea freight forwarding, the interplay between the House and Master Bills of Lading is not only common but essential. It allows forwarders to bundle multiple small shipments (less than container load or LCL) into a full container load (FCL) and manage cargo more efficiently. But it also introduces some complexity.

Since the MBL shows the freight forwarder as the shipper and consignee, the shipping line isn’t concerned with the final customer. Their relationship is solely with the NVOCC. The freight forwarder, meanwhile, has a direct contract with the end customer via the HBL. Any misalignment between the two documents — for example, discrepancies in cargo description, port of destination, or the consignee’s details — can result in clearance delays, penalties, or even cargo being held up at the port.

This is why documentation accuracy is so critical in sea freight forwarding. Any mistake can have ripple effects that impact transit times, costs, and customer satisfaction.

Why the distinction matters in sea freight forwarding

So, why does the difference between HBL and MBL really matter in sea freight forwarding? First and foremost, it impacts liability. If cargo is damaged or goes missing, who is responsible? The carrier will refer to the MBL and address claims with the freight forwarder or NVOCC. The customer, in turn, deals with the freight forwarder based on the HBL. Therefore, understanding the chain of responsibility helps in risk management and claim resolution.

Secondly, it matters for customs clearance. Some customs authorities require submission of the MBL for clearance, while others work with the HBL. If you’re not aware of what document is needed in your destination country, your cargo might end up sitting at the port longer than expected, incurring demurrage fees and other charges.

Lastly, the difference affects flexibility and control. Freight forwarders using HBLs have the ability to control the release of cargo. They can require original documents for cargo release or use electronic methods. This enables them to ensure payment is made before the cargo is delivered, which is crucial in international trade where parties may not always trust each other fully.

Real-world examples: When confusion creates chaos

Imagine a scenario where an exporter in Vietnam ships garments to a buyer in Germany. The exporter works with a local freight forwarder, who issues an HBL naming the German buyer as the consignee. The forwarder books space with an ocean carrier, receives the MBL, and lists itself as both shipper and consignee. However, upon arrival in Hamburg, the buyer presents the HBL for cargo release — but the carrier only has the MBL on file. Without proper communication or documentation, the cargo cannot be released, leading to delays and financial losses.

Another example might involve a dispute over cargo condition. If a claim is filed, the carrier will refer to the MBL terms, which might limit their liability. The customer, however, may have expected broader coverage based on what was written in the HBL. This mismatch can lead to legal wrangling and strained business relationships.

Bridging the knowledge gap for shippers and forwarders

Understanding the difference between House and Master Bills of Lading isn’t just about being a better-informed shipper — it’s about ensuring smoother operations, lower risk, and more reliable outcomes in international logistics. Whether you’re handling full container loads or consolidated shipments, being clear on who issued what document — and to whom — can mean the difference between a seamless shipment and a logistical nightmare.

For companies involved in sea freight forwarding, training teams to understand both documents, ensuring documentation accuracy, and maintaining clear communication with partners can reduce errors and speed up customs clearance and cargo delivery.

Final thoughts: Managing the sea of paperwork

In today’s fast-paced global trade environment, knowing your documentation is a competitive advantage. The House Bill of Lading and the Master Bill of Lading serve different masters, but both are critical in the choreography of international shipping. Freight forwarders, shippers, and consignees must all understand their respective roles and responsibilities as defined by these documents.

For professionals in sea freight forwarding, mastering the distinction between HBL and MBL is not just about compliance; it’s about control, confidence, and credibility in the supply chain. Whether you’re new to the game or a seasoned veteran, revisiting these fundamentals can keep your shipments sailing smoothly across international waters.